Methodology

WHAT IT IS

The Justice Snapshot is a rapid justice assessment, designed to enable local teams deployed on the ground to collect data across the justice system within a narrow time-frame (3 months). It engages with justice stakeholders and national authorities to produce a common evidence base for planning and costing short, medium and long term reforms in the justice system, while providing a monitoring and evaluation framework to measure progress.

Experience shows that justice data may be scattered, but they exist. The Justice Snapshot combines data collection, surveys and practitioner interviews within an accessible and easy-to-update website that anchors system stabilization in reliable baseline data and encourages national institutions to invest in data collection to inform and streamline their priorities for programming.

The data are collected for a 12 month period against an agreed cut-off date. In this Justice Snapshot of Ethiopia, the data are for the financial year from Hamle 1, 2012 (E.C.) to Sene 30, 2013 (E.C.), in line with the Ethiopian Calendar (E.C.). This corresponds to July 2020-July 2021 in the Gregorian Calendar.

WHAT IT DOES

The Justice Snapshot sets in context the environment within which justice operates. It depicts the way the justice system is designed to function in law, as compared with how it appears to function in practice; it captures the internal displacement of people due to conflict or environmental hazard, which could place unmanageable case volume pressures on the system; and it shows the money and external funding available to support the operation of the justice system.

The Snapshot provides a library of reference documents, from the laws in effect to national policy documents and project papers and research / academic studies, to provide a ‘go to’ resource. It enables users to cross check the data used in the visualisations with the source data in the Baseline.

Most importantly, it leaves national authorities and development partners with greater analytical and monitoring capacity than when it began. By embedding the vast array of information that has been collected, analyzed, and visualized within a website, the Snapshot can be updated to establish an increasingly accurate repository of data to inform both justice policy and the strategic interventions needed going forward.

WHY IT WORKS

It provides context, bringing together information about: what practitioners say about working in the justice system, as compared with what users of the system have to say about their experiences of it; the dislocation of large numbers of people; and the funding envelopes available to deliver justice generally and by institution. These data may better inform responses to provide justice and other social services where they are needed most.

It measures impact, compiling data from the most elemental level of individual police stations, courthouses, and prisons to identify weaknesses or gaps in personnel, infrastructure, and material resources. This enables state planners and development partners to assess and address highly strategic building, equipping, and training needs and to monitor and evaluate incremental progress over time so as to scale up what works and remedy what does not.

It is accessible, quick and transparent, applying a tried and tested methodology and using live, interactive, visualizations to accentuate nuances in data, instead of a static report; while signaling discrepancies through data notes and making all source data available to users.

It is collaborative and transferable, engaging the justice institutions from the beginning in collecting and analyzing their own data to stabilize justice system operations. It is objective and apolitical, generating a series of data-drive accounts of the functioning of the justice system, ranging across security and migration to infrastructure/resources, case-flow and governance – and weaving them together to illustrate how the whole of a country’s justice system is functioning, giving national authorities the tools to inform their interventions, rather than policy prescriptions.

HOW IT WORKS

The data are collected from each justice institution (police, prosecution, legal aid providers, judiciary, prison) with the consent of the principals of each institution. The data are owned by the respective institutions and are shared for purposes of combining them on one, shared, site.

The methodology applied in the Justice Snapshot derives from the Justice Audit. The Justice Audit is distinguished from the Justice Snapshot in that the former takes place over a longer period of time and is able to serve as a health check of the justice system. It engages with governments to embark jointly on a rigorous data collection, analysis and visualization process to better inform justice policy and reform.

As with the Justice Audit, the Justice Snapshot does not rank countries, nor score institutions. Instead, it enjoins justice institutions to present an empirical account of system resources, processes and practices that allow the data to speak directly to the stakeholder. The GJG and Justice Mapping have conducted Justice Audits at the invitations of the Malaysian and Bangladesh governments.

The data collected in the Justice Snapshot comprise a breakdown of each institution’s resources, infrastructure and governance structures – and track how cases and people make their way through the system. All data are, in so far as it is possible, disaggregated by age, gender and physical disability. And all data are anonymised and Personally Identifiable Information (PII) removed.

These administrative data are triangulated with surveys of justice practitioners (police and prison officers as well as judges, registrars, prosecutors and lawyers) and court users (people coming to the courts for redress whether as defendants, victims, witnesses, or family members).

The regional baseline data sets are collected by independent research teams and enumerators under the guidance and with the support of the Justice Snapshot Steering Committee (JSSC) in each region – members of which are nominated by their principals in each justice institution. Once the institutional data are collected, they are cleaned of obvious error. Any gaps in data are indicated ‘No Data’ unless the data show, for instance, 0 vehicles. Where the accuracy of data cannot be verified, or require further explanation, these are indicated in the ‘Data Note’ box. The clean data are then submitted to the JSSC for validation and signed off by the institutions concerned. The cleaned data sheets appear by institution in the Baseline Data as these are the data visualised throughout the Justice Snapshots.

Note: the data captured will never be 100% accurate. Gaps and error will occur especially in this first Justice Snapshot as those working on the frontline of the justice system are not used to collecting data systematically and especially not on a disaggregated basis. However, data collection and accuracy will improve over time and as systems are embedded within each institution.

The data are then organized and forwarded to Justice Mapping who design the visualisations based on the data and populate the visuals with the data. Both the Justice Audit and Justice Snapshot are designed to be living tools rather than one-off reports. The purpose is to capture data over time and identify trends and so monitor more closely what works (and so scale up) and what does not (and so recalibrate or jettison).

The data identify investment options in the Action Matrix to inform the UN joint agencies own programmes, sharpen budgetary allocations and improve aid performance for ‘Better Aid’ (and more joined-up justice services). These investment options are also aligned with government and institutional development plans.

HOW DATA MAY BE UPDATED AND SUSTAINED

The engagement with key institutional actors at the outset is not just a courtesy. The methodology aims to maximize the participation of all actors and encourage them to invest in their own data collection better to inform policy for the sector as a whole and leverage more resources for their own institution. From the moment it is formed, the JSSC takes ownership of the process, and so is central to this approach.

Following this Justice Snapshot, it is intended that each JSSC (and State Councils as well as Federal government) will encourage their respective institutions to collect disaggregated data, at regular intervals, using standardised data collection sheets. These data will be reported in line with existing procedures up the chain – and to an information management unit (IMU), or units, to conduct successive Justice Snapshots going forward at 1-2 year intervals to monitor change over time. The law schools who led the data collection would be available to provide backstopping and technical support as required.

Each Justice Snapshot follows a six-stage process:

- Planning

- Framing

- Collecting

- Interrogating

- Designing

- Validating

| Stage | Action | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov |

| PLANNING | Desk review, contracting, first iteration | |||||||

| FRAMING | Shapefiles, Data collection forms, survey q’aires, Inception report, second iteration | |||||||

| COLLECTING | Phase I: location of justice services, data integrity check, formation of Justice Snapshot Steering Committees (JSSCs): federal and regional levels (9 regions) and Chartered Cities Phase II: JSSC meeting 1 to launch population of justice services (institutional data collection) in 9 regions + Surveys: Practitioners and Court Users in 2 regions | |||||||

| INTERROGATING | Data cleaning + formatting. JSSC meeting 2 to validate institutional data. Data analysis + draft commentaries | |||||||

| DESIGNING | Justice Mapping design visuals for representing data collected + third iteration | |||||||

| VALIDATING | Presentation of draft Rapid Justice Assessment to UN agencies and national stakeholders, fourth iteration. Incorporation of comments / feedback: final report and assessment. |

1. Planning

The GJG was contracted on 3 May 2021 through to end September 2021. UNDP commissioned the work on behalf of a Technical Working Group (TWG) made up of: UNDP, UNODC, UNICEF, UN Women, UNOHCHR and UNHCR.

At the time:

- national elections had been delayed and a revised date in early June was further revised to 21 June.

- The issuance of visas for outside visitors was suspended on 18 June and remained in effect up until the time data had been collected (early September).

- Conflict in the north (Tigray) was ongoing and spreading into neighbouring regions (Afar and Amhara) and emerging as a civil war.

- The Courts were on vacation (June-September) open only for urgent family and criminal cases.

- The COVID pandemic was also active.

Notwithstanding this context and GJG observations to the Joint UN Agencies, this assessment already long delayed was instructed to proceed. Due to time lost as a result of the elections, an extension was granted until 30 November 2021.

In view of the dislocation of team members due to the factors bulleted above. A core team was established in an office in Addis Ababa led by Dr Alemu M Negash with three project assistants (two of whom lawyers and one data specialist). He and his team were supported by two senior advisers (both law professors) and a senior adviser on gender and child justice (and former judge of the High Court) – as well as the team leader and data analysts in Portugal and project manager in London, UK.

From the outset, weekly meetings were held by Zoom with all team members and on a daily basis by WhatsApp between the project manager and project assistant in Addis and project team leader and team lead (Addis).

The presence of senior law professors on the team facilitated access to the network of law schools across the country. Following letters to the Deans of Law Schools in all regions, law professors were nominated. Over 60 contracts were drawn up with law professors, assistant lecturers and students from the Universities of:

- Addis Ababa

- Gambella

- Hawassa

- Dire Dawa

- Assosa

- Haremaya

- Semera

- Bahir Dar

- Jijiga

- Arsi

- Debre Birhan; and

- Jimma

Regrettably, the difficulties of communication with Mekelle in Tigray prevented inclusion of that region in the assessment.

All contractual and financial matters were handled by the Project Assistant in Addis and the Project Manager in London. All content matters were handled by the Addis team lead and project team lead in Portugal and ratified by the senior advisers.

The GJG reported to the UN Technical Working Group (TWG) made up of UNDP, UNODC, UNHCR, UN Women, UNICEF and UNOHCHR and communicated regularly with the TWG co-chairs from UNDP and UNODC.

It was agreed at the outset that a problem-driven iterative adaptation (PDIA) approach would be adopted to provide flexibility to the project team in navigating the elections and allowing for progress to be made notwithstanding ongoing events within the country.

Example: first meetings with key stakeholders to seek their consent to the research and nomination of their representatives on a federal JSSC were not practicable. It was assumed in consultation with UNDP that since they had approved the ToRs earlier and appointed a Justice Sector Coordination Committee (JSCC) made up of senior office holders, the research could start. A first introductory meeting with the JSCC could not be convened until early in September (when the data collection was already advanced).

It was further agreed that iterative versions of the assessment be shared throughout the assessment period. During these presentations, the UN TWG and UN HoAs were able to see and comment on the direction / approach of the assessment team and further clarify their expectations to the team. Given the time-frame and disruption to it caused by the elections, there was broad acceptance that what was desirable needed to be balanced with what was feasible; and insistence by the UN Agencies that the visualizations of the data (on a web-based platform) would need to be further supported by a narrative text.

Getting to work…

A desk review was conducted of available material. A team of law students in the Bluhm Legal Clinic of Northwestern University used their search engines to source materials for the review and prepared summaries of them.

Government’s 10 Year Perspective Development Plan, The Pathway to Prosperity 2020-2030 and the Federal Justice Institutions own ‘Common Agenda’ were obtained and studied for policy direction and identification of priorities.

Annual reports produced by each institution (federal and by region) were also sourced and translated – along with their strategy plans where available.

The materials were uploaded on to a Library.

UNOCHA were approached for Shapefiles which were promptly provided to Justice Mapping to map the country by region and zone.

UNHCR provided their data on populations of concern to show the movement of people in and around the country.

The open source data of the Ministry of Finance showed the income and expenditure for the financial year 2012-2013 (Ethiopian Calendar) – equivalent to 2020-21 in the Gregorian Calendar.

The Feteh Project under USAID was approached and the ToRs of the Assessment were shared. Cooperation was explored but the timelines were at variance and it was agreed that the assessment should proceed alone.

Within six weeks, the team was able to present to the UN TWG and their Heads of Agencies what the assessment would look like.

2. Framing

Institutional Data Collection (IDC) forms were developed by:

- geography (down to the woreda level); and

- institution (by four dimensions: infrastructure, resources, case management and governance).

Gender, age and disability were mainstreamed in the data collection across the dimensions above.

Further adaptations were made in view of the literature reviewed, the emphasis in the Terms of Reference and consultations with senior advisers.

IDC Forms were developed for: Police, Office of the Attorney-General, Office of the Public Defender, University Legal Clinics (ULCs), NGO Legal Aid Service Providers (LASPs), Courts (both federal and regional at all levels, including City and Sharia Courts) and Prisons.

The Forms were designed to capture key data points that collectively indicated the gradation of challenges facing justice service providers in any given Zone in the country and so flag to the viewer areas for priority action.

Survey questionnaires and Court Observation forms were also developed.

The IDC Forms collected institutional data. These are subject to challenge in terms of accuracy and reliability, so they are further viewed against – or triangulated with – survey data and appear in Situation Overview, Justice in Practice.

The first is an earlier general population survey carried out by the Hague Institute for Innovative Law (HiiL) extracts of which appear in Justice in Practice (the full report is in the Library).

The next two are surveys conducted of Practitioners (ie the justice service providers: the police, prison police, judges, registrars, public prosecutors and lawyers) and Court Users (ie the justice seekers: civil complainants and victims, civil defendants and criminal accused, witnesses and family members). Questionnaires were drawn up in consultation with senior advisers and field tested and then translated for application in two regions.

Additionally, Court Observation forms were developed for woreda and zonal courts, as well as for social / City courts and the juvenile court in Addis Ababa. The results are commented on but not visualized (and appear in the Baseline data) as the woreda and zonal courts were on vacation and observations were limited to 19 woreda courts and 12 zonal courts and limited in caseload.

These survey data were then analysed to produce a picture of how justice services appear to work in practice across Ethiopia.

The Surveys and Court Observations were conducted by two teams each in Oromia and Amhara regions. Oromia has 21 Zones and Amhara has 12 Zones. Six Zones were selected for the survey catchment areas in each based on geography: rural, peri-urban, urban.

Teams were formed under a law professor from the universities of Bahir Dar and Debre Birhan (Amhara) and Jimma and Haramaya (West and East Oromia) and included 10 students in each team supervised by the law professor.

The survey questionnaires and court observation form were each subjected to cognitive and field testing in Addis. The questionnaires and forms were translated into Oromifa and Amharic and then back translated to ensure the sense was maintained.

3. Data Collection

Phase I identified the location of justice services in each region, save for Tigray (down to Woreda level), Chartered City (down to the Social Courts) and at federal level. Phase I aimed to identify whether the presence of justice services was an active presence. Team leaders were briefed and provided with a short guidance note to share with their teams:

Location Services Population: Supplementary information

- This document provides supplementary information for Phase I of the data collection process (the Location of Justice Services).

- It provides further questions going to what is meant by the terms: ‘operational’; ‘functioning’; and ‘active’.

- The answers of which inform whether the researcher enters a ‘1’ (yes) or ‘0’ (no).

- I.e Police station is operational = 1. Police station is not operational = 0.

- ‘Operational’ Police Station

- Is the Police Station open to the public (i.e can an individual go there to report a crime)?

- Is the police station staffed?

Example: The physical infrastructure of the police station exists, but it is not staffed.

Answer: The Police Station is not ‘operational’ so enter: 0

- ‘Functioning’ Woreda/Zonal/Regional Supreme Court

- Are Judges sitting?

- Are cases being heard?

Example: The physical infrastructure of the court exists, but no judges are sitting.

Answer: The court is not ‘functioning’ = 0 (no)

- ‘Active’ Prosecution Office

- Is the Prosecution office occupied by a prosecutor?

- If there is an office but no prosecutor allocated to that office = 0

Example: A prosecutor is not stationed at the Woreda but appears regularly on circuit.

Answer: There is an ‘active’ prosecution office = 1 (yes)

- ‘Active’ Legal Service Provider

- Is there an NGO or University law Clinic providing legal services in the woreda?

Example: There is an NGO which provides legal assistance once a week.

Answer: They are ‘active’ legal service providers in the Woreda = 1 (yes)

- ‘Active’ Public Defender’s Office

- Is there a PD allocated to a Woreda?

Example: No physical infrastructure but a Public Defender appears regularly on circuit.

Answer: There is an ‘active’ Public Defender = 1 (yes)

- ‘Functioning’ Regional Prison

- Is the prison staffed and does it hold prisoners?

Example: The physical infrastructure exists but there are no prison officers based there.

Answer: The prison is not ‘functioning’ = 0 (no)

The teams also conducted short ‘Data Integrity Checks’ to understand how data are generated at source, stored (on paper – PAPI – or in computer files – CAPI) and communicated up the chain of command. The Data Integrity Check also sought to understand if data were made public (ie through Annual Reports).

It appears that all justice services (save for the OPD which is not an independent office and sits in the Supreme Court at both federal and regional levels) produce Annual Reports which most forward to their line Ministries. Most indicate these reports are public (though 4 regional police commissions indicated they were not). CAPI appears to be widely available (so facilitating communication of data to the centre / headquarters) with notable exceptions such as in SNNPR.

The teams also invited heads of justice institutions to nominate their representatives to sit on a Justice Snapshot Steering Committee (JSSC) – their names appear in the Acknowledgements.

Phase II followed immediately on the back of Phase I. The purpose was then to apply the IDC forms and collect data against the justice services identified in Phase I. Data on infrastructure and resources were collected up to Zonal level and data on security, case management and governance were collected at the Regional level. The data were sourced from the institutional regional headquarters from the person responsible. So, for instance, case data in the courts were sourced from the registrar of the Supreme Court or someone in his/her office. Human resource data from the person responsible in the regional police commission. Data on infrastructure from the institution’s planning officer etc. Each team accompanied the data with a list of the sources from which the data came. In a number of instances, the case data were sourced from the Annual Reports. Sources are not named to protect Personally Identifiable Information (PII).

The law professors and lecturers came to Addis Ababa for a Roundtable meeting to review the IDC forms between 13-16 August. The forms were then translated into Amharic and circulated. The law professors and lecturers recruited two senior students to assist the research. They were provided with guidance notes to assist them:

- General

- The data collection builds on the work you did earlier and seeks to populate the justice services you located in Phase 1.

- During Phase 1 we identified the locations of each justice service down to the woreda level.

- We now seek to aggregate the services in each Zone as concerns their infrastructure and resources and at the regional level as concerns security, case management and governance.

- People to be approached

- They should be the same people you spoke to in Phase 1. They will then indicate the appropriate person to contact in terms of the data collection process.

- The Justice Snapshot Steering Committee (JSSC) you formed in Phase 1 (with the persons nominated by each institution) should now start to perform its task, namely, to guide and support you and your team in this research.

- The data

- The data fields are not exhaustive as this is a Rapid Justice Assessment.

- They are more strategic and aim, once triangulated with survey and observation data, to provide a broadly accurate picture of how the justice system functions at federal, regional, and chartered city levels.

- Types of data

- In FORM ‘A’: We are collecting data for (1) Infrastructure, as well as (2) Human and (3) Material Resources aggregated to each Zone.

- In FORM ‘B’: We are also collecting data for (4) security, as well as (5) case management and (6) governance, including training aggregated to each region.

- These six types of data, and their respective forms, appear for each institution.

- Sources of data

- All data should be sourced if it is to be credible or carry any weight.

- A ‘Source Identification’ form is provided that should be completed.

- If possible, data should be cross-checked. This means identifying opportunities where data verification is possible.

- For instance, Woreda-level material resources may not be independently verifiable, but the number of RFIC Judges may be. Likewise, the number of pending, new and disposed cases in the year.

- If a response is precise – we should ask what is the independent verifiable source for that figure? (e.g… Annual Report)

- If a response is not precise, then an estimate should be indicated and we should ask the basis for this estimate (e.g… institutional policy, recent visits, and direct observations, or simply belief).

- The bottom line is that the time and resources of this research do not allow for independent verification, we rely on the data received from each institution and validated by the JSSC.

- Data Collection Forms

- Each form type (A or B) contains the same types of data and follows a broadly similar sequence of data fields.

- For Form A, a maximum of 5 Zones are captured. If there are more than 5 Zones in a given Region, there will be more copies of Form A.

- For Form B, given it asks questions at a regional level, there will only ever be one copy.

- Data Collection Process

- Forms should be printed and distributed to the student researchers.

- The students will complete the forms with the relevant institutional representative.

NOTE:

1. Not every zone will have a Regional Supreme Court. The researcher should strike through the response (e.g YES / NO) on the form.

2. Where there are no data for a field, for instance the interviewee shrugs when asked a question, or says s/he does not know the answer, the researcher will enter: ‘-99’.

3. Where the interviewee is asked, for example, the number of Woreda courts with access to internet and the answer is none of them, the researcher will enter: ‘0’.

- They will submit the forms to the supervising law professor who will spot check the form to ensure:

- (1) all fields are completed;

- (2) there are no evident outliers or mistakes; and

- (3) the law professor will retain the forms in hard copy.

- The data will be entered into the ‘Consolidated Data Entry Sheet’ (in Excel) and sent to Dr Alemu M. Negash and his team in Addis Ababa.

- Data Cleaning

- The data will be reviewed by the GJG in Addis Ababa and in Europe. Where there are queries over, or gaps in, the data, these will be communicated through Dr Alemu and his team to the regional team concerned to answer.

- Once cleaned, the data will be returned to the regional team who will share the data with the JSSC for validation.

- Data validation

- This is an important phase. Data must be validated by the institution concerned for that region. This not only ensures the institutions do not reject the published data but protects the research teams from allegations that the data are made up.

Once the data are validated by the JSSC, the work is complete!

The teams met with the regional JSSC for lunch to introduce the students, share the IDC forms and present the workplan during the week-end of 21-22 August. They then deployed to collect the data.

On 2 September, the Federal Justice Sector Coordination Committee (JSCC) convened in Addis to hear a presentation from the full GJG team on the proposed approach to the assessment. The JSCC clarified to the team that the output should pay particular attention to the Common Agenda set out by the JSCC.

The law professors and lecturers from Oromia and Amhara were briefed on the survey questionnaires at a roundtable meeting in Addis (22-24 August). Comments were recorded and the necessary changes made to the questionnaires. The target numbers of Court Users, Practitioners to interview and Courts to observe were agreed to arrive at clusters of each that provide a useful sample. Emphasis was placed on the ethics of field work (with which team leaders were familiar) and the importance of obtaining informed consent before starting any survey. A short user manual was provided to the teams to guide them in their work:

I. Basic Standards for data collection

The interviewer is expected to observe the following at all times:

- Be courteous towards everyone.

- Do not disturb or upset anyone with your behaviour. Remember that people might be watching you (or able to hear you) even when you don’t realize it.

- Always carry your letter of introduction.

- Dress in a respectful manner.

- Turn off your cell phone during the interview.

- Do not eat, drink, or chew gum during the interview.

- If you make an appointment, you must arrive at the stated time. Respondents should never be kept waiting.

- Remain neutral: never look like you are shocked, surprised, disappointed, or pleased with an answer.

- Do not change the wording or sequence of questions. Everyone needs to be asked the same question in the same order.

- Be patient with the respondents. Many respondents may have low education levels. Be respectful if they become confused or need something repeated.

- Ask your supervisor if you have any questions or doubts during an interview or need clarification on any section of the questionnaire.

- Complete all questionnaires thoroughly in the field. At the end of each interview, check the questionnaire for completeness and accuracy.

Always thank people for their time, even if they chose not to participate.

II. Data Collection: Procedure for Court User and Practitioner Surveys

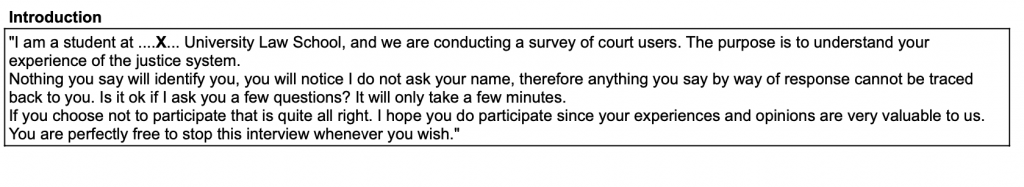

1. Reading the Introduction

⇒ It is very important that you read the introduction section to the potential respondent.

⇒ When you read the introduction, though, try to look up and make eye-contact with the respondent. This is a good way to build rapport with the potential interviewee.

2. Consent

⇒ Only start a survey if the person being interviewed has been read the consent statement and has given their consent to participate. If the respondent does not consent, thank them for their time, and move on. Remember, we are only able to get someone’s consent if they are over 18 years old and of sound mind.

3. Name and Phone Number

⇒ We will not be collecting the name or phone number of the respondent.

4. Privacy

⇒ If you are not alone with the respondent, you should ask whether there is a place where you can speak in private. If the person refuses, or if there is not a private place, it is ok to conduct the interview in front of others if the person agrees.

5. Reading Answer Choices

⇒ Please note, none of the answer choices are secret – if the respondent would like the choices read you should read it to them.

6. Collecting Answers

⇒ It is important that the interviewer report any answer that the respondent gives. The function of the interviewer is not to judge the respondent, teach the respondent, or uncover if the respondent is telling a lie.

7. Answer Right Away

⇒ The questionnaire should be completed on site. You must not record the answers on scraps of paper with the intention of transferring to the application later. Neither should you count on your memory for filling in the answers once you have left the court area.

8. “Other” Responses

⇒ For some of the questions, it is foreseeable that the respondent will give an option other than the ones that are coded. If this is to happen, write in the other response in the language in which it is given.

9. Avoiding “I don’t knows”

⇒ Most people have an opinion on most issues, they just need to be empowered to share their opinion and encouraged to take the time to think about it. If someone tells you that they “do not know” the answer to a question, remind the person that his/her opinion is very valuable to us and ask if he thinks having a few moments to think about the question further would be helpful.

10. Ending the Interview

⇒ Make sure to thank the respondent when the interview has concluded.

COURT USER SURVEY

I. Data Collection: Input

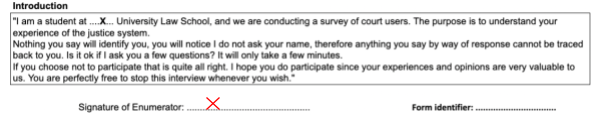

1. On beginning the court user survey, the researcher must read out the informed consent statement and indicate that they have done so by signing the form.

2. After reading out the informed consent, and signing the form, the researcher must put in a form identifier.

a. This will be the initials of the researcher, the initials of the University, the acronym for the form, and the number of the form.

- Name of researcher = Finn Stapleton English (´FSE)’

- Name of University = Jimma University (‘JU’)

- Name of form = Court User Survey (‘CU’)

- Number of the survey = if it is my FIRST survey, then 1, if it is my 13th survey, then 13 (‘1’)

3. The researcher is to ‘X’ one of the coded responses for each question.

See example below

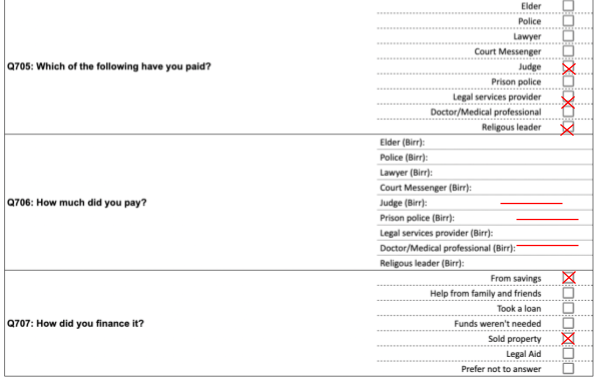

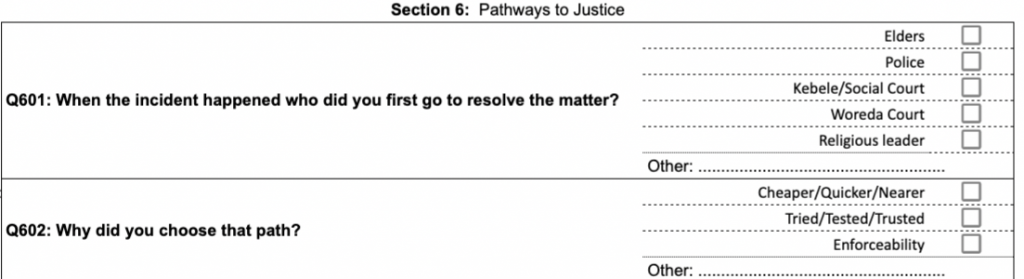

4. There are exceptions to the singular option.

⇒ Here the questions shift and are meant to capture multiple responses.

⇒ List of questions where multiple options can be recorded:

- Q202;Q403;Q405;Q602;Q702;Q705;Q706;&Q707

See example below.

- As mentioned, the answers are not secret, the researcher may prompt the respondent (see example below)

Enumerator: “Q602: Why did you choose that path?”

Enumerator: “Because it was cheaper, quicker or nearer? Or perhaps it is because you trust the system?”

III. Data Collection: Consolidation

- Once the data collection has been completed, or during its completion, the hard copies of forms will need to be input into soft copy.

- An excel ‘consolidation’ sheet will be provided – see instructions (separate document)

- Each Court User form will need to be manually inserted into this document.

- Especially important to remember the FORM IDENTIFIER (i.e FSEJUCU1)

- Send completed consolidation sheet to GJG teams in Addis

PRACTITIONER SURVEY

I. Data Collection: Input

1. On beginning the Practitioner Survey, the researcher must read out the informed consent statement and indicate that they have done so by signing the form.

2. After reading out the informed consent, and signing the form, the researcher must put in a form identifier.

a. This will be the initials of the researcher, the initials of the University, the acronym for the form, and the number of the form.

- Name of researcher = Finn Stapleton English (´FSE)’

- Name of University = Jimma University (‘JU’)

- Name of form = Practitioner Survey (‘PS’)

- Number of the survey = if it is my 13th survey, then 13 (‘13’)

COURT OBSERVATIONS

Notes

1. You are an observer. There are no interviews with anyone. You enter only what you directly observe.

2. You may feel more comfortable by informing the presiding judge what you are doing and the purpose. However you do not require permission as the court should be open to the public. This means to anyone. If you are not allowed in, identify the court as per section 1 and fill in Q201 with NO. Then leave.

3. Public Access and Security. Sit in the court and complete these questions. If you wish to add any further notes do so and attach them to the form. Please compile all these notes at the end and submit to your law professor who will share them with the office in Addis Ababa.

4. User friendliness. Walk around and complete the questions from 301-313. Again add any notes if you wish.

5. Type of court. We are more interested in the criminal cases, so please spend most of the time in the criminal bench.

6. Process. Sit in the court until it adjourns (for lunch, or the end of the day). With each case please make a note covering the questions.

401 – If in a language other than Amharic or Oromifa, please note it.

402 – Can you see someone operating a machine? If proceedings are not recorded, leave 403 blank.

404 – It may be you observe a number of hearings and only one person (out of this number) had trouble following things. If so, circle ‘Yes’ and note 1 / 5 (or the total number of persons you observed give evidence) and add a note that ‘generally most…’ or ‘very few…’ understood the proceedings. If no one had any trouble, circle No and leave 405 blank.

406 – are there any speakers to amplify what is said, or other visible aid that people with hearing problems can see? If you cannot see anything that might assist people with hearing problems, circle No.

407 – is there a sign anywhere that indicates to people they can seek assistance with interpretation? If not, circle NO

408 – were the proceedings conducted formally and in line with civil or criminal procedure?

409 – if 0 children appeared as parties, enter No and leave 410 blank.

411 – did you see the judge refer to a law book? Could you see if s/he had access to any law books (ie on the bench)?

412 – Add up the total number of cases you observed in the session and enter the figure.

413 – if they were all criminal cases, enter the same figure as in 412.

414 – Note each criminal case whether the defendant was represented by a lawyer. If the person is represented, leave 415 blank.

415 – Did the judge or clerk or other person appear to hurry the defendant along or put pressure on him/her to get a move on.

416 – In criminal cases, did the accused in the dock appear under any form of restraint? For instance, handcuffs, leg irons, rope or other?

417-9 – These questions go to the atmosphere in the court and whether the proceedings were conducted fairly, equally and respectfully. This is more subjective and should be guided by the treatment of the accused (was s/he pushed into the dock or dragged out of it), the tone of the judge, whether s/he interrupted or raised his or her voice; and whether the judge favoured the prosecution over the defence?

420 – Record the sentences ordered by the court in front of you on the day of your visit

421 – similarly record the judgments ordered by the court.

The surveys do not claim to be representative (unlike the HiiL Justice Needs and Satisfaction survey). They are offered as ‘purposive’ surveys and the weight given to each will be determined by the viewer. The Court User surveys were conducted at Woreda and Zonal Courts selected on the basis of location (a mix of rural, urban and peri-urban) in two regions. As noted above, the courts were on vacation and only dealing with urgent cases in the main family and criminal matters.

All data collected (both institutional and survey) were spot-checked by the team leaders and checked for gaps, obvious error and outliers. Each survey and court observation form carried an individual identifier for the student who conducted the survey / court observation.

4. Interrogating

The institutional data collection forms began coming in on 6 September and the process of cleaning them started.

The GJG methodology is as follows: the raw data is retained untouched in a folder (in Google Drive) and a new folder opened (Data Cleaning). The raw data are copied to the new folder and the data are then checked.

Numerous sets of eyes review each piece of data. The first is the Law professor or lecturer supervising his/her students and looking out for gaps and obvious error before s/he submits the data to the team in Addis. The raw data are then sent to the GJG team. Two team members check the data. The first eyes check each data value:

- for internal inconsistency (within data subsets as well as across institutions, ie police investigation reports sent to OAG and OAG record of investigation reports received from police); and

- against institutional Annual Reports and other available documentation.

The second eyes review the data again and the comment of the first eyes and either adds to it or indicates the date seen. The data are then sent back to the GJG team leader in Addis who reviews again before sending back to the data collection team leader to respond. The response is entered in the excel sheet in the column provided and a decision is then made on the data. An example is set out below:

| Eyes 1 | Eyes 2 | Response | Decision | |||

| e3_number new cases in 2020/1 (total) | 1220 | MB: In e5 in police B the number sent to prosecutors by police was 386 | AS 0709 | Response puts this down to federal and traffic cases which the PPs investigate not police. | Insert Data note, reads : Police record 386 investigation files sent to OAG. | |

| e4_number Investigation files in 2020/1 (total) | 1641 | MB: Police only investigated 425 (see e3 in police B) | AS 0709 | Insert Data Note, reads: OAG also conduct investigations (with police) into traffic accidents and federal cases. |

The decision may be to amend the data originally captured if the response is satisfactory, or enter ‘-99’ to indicate the data is either unavailable or wholly unreliable, or replace with data from the Annual Report. Data Notes (as shown above) are written to inform the viewer of data mismatches or discrepancies allowing the viewer to determine what weight s/he will give to the data represented.

All institutional data received were cleaned in this way. Once cleaned, the data were transferred to a new ‘Cleaned’ folder in the G Drive. These data were then formatted, cleaned of all comments, queries and responses and left only with the data and any Data Note. These data sets were then sent to the team leaders in each region to share with their JSSC for validation (ie that the data represent the best available as shared by the institutions with the data collection teams). The data were validated either by a meeting of the JSSC or individually by each institutional representative and the data signed off by them, as follows:

- Afar: 30 September 2021

- Amhara: 4 October

- Benishangul-Gumuz: 5 October

- Gambela: 28 September

- Oromia: 15 October

- SNNPR: 30 September

- Sidama: 30 September

- Harari: 7 October

- Somali: 19 October

- Federal: 28 October (save for the Federal Police and Federal Sharia Courts*)

- Addis Ababa Chartered City: 28 October

- Dire Dawa: 1 November

*Note: The Federal Courts of Sharia did not validate their data, not due to disagreement with the data but due the time needed to do so. Federal and City police did not participate in the assessment research either in Addis Ababa nor in Dire Dawa.

Once validated, the data sets are sent to Justice Mapping for uploading on the web platform where they are again subject to scrutiny by the Justice Mapping design team.

Survey data were not cleaned but formatted and analysed. They included:

- 494 practitioner surveys (including 142 women respondents – 29%)

- police total: 119, including 43 women

- prison police total: 61, including 16 women

- RHC judges total: 41, including 5 women

- RFIC judges total: 65, including 13 women

- RHC Registrars total: 31, including 7 women

- RFIC Registrars total: 21, including 14 women

- Lawyers total: 63, including 11 women

- Prosecutors total: 93, including 33 women.

- 643 Court User surveys (including 240 women – 37%)

- civil complainants: 129, including 75 women

- civil defendants: 108, including 24 women

- criminal victims: 88, including 44 women

- criminal accused:150, including 29 women

- witnesses: 78, including 29 women; and

- family members: 90, including 39 women.

- 31 Court Observations of Woreda (19) and Zonal courts (12) + 3 social courts and 2 city courts in Addis Ababa and of the juvenile court in Addis.

These data are not validated, given the nature of them, and are accorded such weight as the viewer thinks they merit. Court Observational data have not been included in the visualization as the operations of the small number of courts observed at the time (on vacation + in COVID) were judged insufficient as a basis for asserting that the view shown was typical of these courts.

5. Designing

The GJG works closely with Justice Mapping (New York). The design work to visualize the data has run in parallel with the assessment and produced iterative versions to share with the UN TWG for comment and input.

The visualization of data (often dense and complex) ensures the viewer can stay in the blue water observing the whole justice system, while at the same time being able to dive down into the weeds to see what is happening there. The viewer is urged to refer back to the Baseline data (the ‘weeds’) to check the view being offered.

Commentaries are included in each visual to provide a narrative account of what is shown. Data Notes also appear to shed light on the data shown. Some (particularly case data) do not appear to make sense. This may be due to error, or due to some intervening element that the data fields did not originally capture (such as ‘reopened cases’). While efforts were made in the cleaning process to explain or rectify these mismatches and anomalies, many remain. This serves to emphasise that data collection and management constitute a process of change and improvement over time.

The use of Red Amber Green (RAG) colours is less to ‘rate’ an institution than to show where there is and there is not the presence of a service. The use of colour elsewhere is to illustrate the gradation of challenge facing a justice service and whether the challenge is High, Moderate or Low. This is intended to aid decision makers and those responsible for identifying priorities and allocating budgets to reform and support programmes.

The Action Matrix is the result of a gap analysis of the data collected (institutional and survey) as well as the weaknesses mentioned in the Justice Institutions’ Common Agenda and challenges mentioned in institutional Annual Reports. It harnesses data driven recommendations behind policy objectives.

The Roadmap signposts the way forward in monitoring progress against policy targets and programme goals and activities set down in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) all countries have signed up to, the Government’s own development plan (The Pathway to Prosperity 2020-2030), the federal justice institutions’ ‘Common Agenda’ and the UN’s Strategic Development Country Framework.

In other countries, Justice Mapping have made this tool updateable. This version is not (for reasons of time and available budget). An offline version is available. The report can be printed as a pdf document.

6. Validating

The UN TWG envisages a process of consultations on the assessment. The report will be shared for comment and feedback at regional and federal levels; and will be discussed in two workshops at technical and leadership levels.

The comments will then be consolidated and returned to GJG and Justice Mapping who will then incorporate them in a final assessment report by the end of November 2021.